Larvicides for fly control in beef and dairy cattle production areas

By Mike Catangui, Ph. D

Fly metamorphosis

House flies (Musca domestica), stable flies (Stomoxys calcitrans), horn flies (Haematobia irritans), face flies (Musca autumnalis) and all other insects belonging to the Order Diptera go through unique sequential life stages to complete their life cycles. In the house fly, for example, adult female flies lay eggs [Fig. 1, A–B] that hatch into first-stage (instar) larvae or maggots within 48 hours at room temperature (68–72°F). These first-instar larvae transform into second-instar, then third-instar larvae [Fig. 1, B–C] within two weeks. Another two weeks are usually needed for third-instar larvae to transform into pupae [Fig. 1, D], and then into adult house flies. Thus, at room temperatures, it takes about a month for house fly eggs to transform and go through three larval stages or instars, the pupal stage, and then into adult house flies.

The immature stages of flies do not look or behave like adult stage flies. Fly larvae have chewing mouthparts; they develop and crawl around manure or any decaying organic matter. Adult house flies have wings, sponge-like mouthparts and alight and feed on sugary and protein-laden liquids. Adult stable flies and horn flies have syringe-like mouthparts and feed on cattle blood. Because fly larvae and adults are quite distinct both in form and function (they follow the so-called holometabolous or complete metamorphosis), different tactics are often necessary to thoroughly control the total existing population of flies in the environment.

What are larvicides?

Larvicides are a group of insecticides specifically labeled to control the larval stages of insects; adulticides are aimed at the adult insects. Because of the difference in the environments where the adult and larval stages of flies are found, the insecticide formulations, application rates, application procedures and equipment will also be necessarily different for larvicides versus adulticides. Liquid larvicides, for example, are applied as a coarse spray over the manure piles; oil-based on-animal fly adulticides are applied as ultra-low volume (ULV) fogs [Catangui, 2019: Spray, Mist or Fog: Get to Know Your Insecticide Application Equipment, Veterinary Update, Spring–Summer 2019, page 98–100].

Contact versus IGR larvicides?

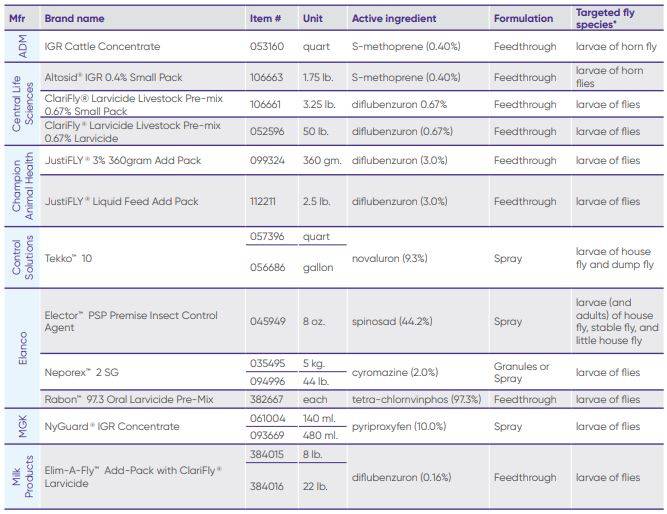

Table 1 lists the larvicides that are currently labeled for use in cattle facilities. Contact larvicides impair the nervous system of the fly larva; mortalities are observed within 48 hours after application. Examples of contact larvicides are Elector® PSP and Rabon™. The active ingredient in Elector PSP (spinosad) is of natural origin; it is derived from the fermentation of a soil actinomycete (a group of soil bacteria) called Saccharopolyspora spinosa. The active ingredient of Rabon is a man-made organophosphate molecule [Table 1]. Because contact larvicides affect the nervous system of the insect, contact larvicides are also adulticides.

Insect growth regulators (IGRs) are designed to disrupt the growth and development of the fly larva [Fig. 1, B–C]. Insect growth regulators are mainly larvicides; they do not cause direct mortalities on the adult stage flies. Mortalities are not observed until the larva attempt to molt and transform into its next life stage. Examples of IGR larvicides are those that contain diflubenzuron, novaluron, cyromazine, pyriproxyfen, and S-methoprene [Table 1]. Diflubenzuron and novaluron are chitin-synthesis inhibitors, pyriproxyfen and S-methoprene are juvenile hormone mimics, and cyromazine is a moulting disruptor (IRAC, 2017).

The effects of insect growth regulators can be better visualized in the pupal stage of the treated flies. Figure 2 shows deformed house fly pupae caused by an insect growth regulator. These deformed pupae were collected from manure that was treated with novaluron (Tekko™ 10). Figure 3 shows deformed or abnormal pupae collected from manure treated with cyromazine (Neporex® 2 SG). Deformed or affected pupae cannot transform into normal flies, thereby causing mortalities in the treated fly populations. Certain larvicides containing the insect growth regulator (IGR) diflubenzuron (ClariFly® Larvicide and JustiFly® Feedthrough) or the contact larvicide, tetrachlorvinphos (Rabon™ Oral Larvicide Premix), can be administered to cattle through the feed ration or supplements (as feedthrough larvicides) [Table 1]. The active ingredients are not digested but excreted as a larvicidal treatment on potential fly breeding sites in and around the cattle production areas.

Summary

Larvicides are insecticides developed for the purpose of causing mortalities in the larval or maggot stages of house flies and other holometabolous insect pests. They are often overlooked in terms of usage and commercial development of new insecticides. Currently, only about 14 percent of all insecticides available for fly control are labeled as larvicides; 84 percent are labeled as adulticides. It is estimated that 80–90 percent of all fly individuals in an environment are in the larval stages; expanded use of larvicides can more thoroughly reduce the total fly numbers in dairy and beef cattle production areas.

Reference: Insecticide Resistance Action Committee [IRAC]. 2017. IRAC mode of action classification scheme. (http://www.irac-online.org/teams/mode-of-action/).

80–90% of all fly individuals in an environment are in the larval stages.

Table 1. Larvicides for use in fly breeding sites in beef and dairy cattle production areas

Prior to using any product mentioned in this article, carefully read and follow all available instructions, warnings and safety information made available

by the product’s manufacturer. See label for use rates. Listed products have zero beef cattle pre-harvest interval or dairy cattle milk withdrawal period.

*Larvae of flies - Larvae of horn fly, face fly, house fly, and stable fly

Fig. 2. Deformed house fly pupae caused by novaluron, a chitin-synthesis inhibitor IGR, beside four normal pupae (on right). (Photo: Mike Catangui)

Fig. 3. Deformed house fly pupae caused by cyromazine, a moulting disruptor IGR. (Photo: Mike Catangui)